Key Points:

UK government revises CfD auction: increased bid caps, offshore wind ring-fenced, new Sustainable Industry Reward (SIR) criteria.

Auction budget for offshore wind may need to surpass £1.5 billion; separate pot risks higher future project costs.

SIR criteria details pending; previous UK regulatory challenges highlight the need for clear, quantifiable evaluation metrics.

CfD design evolution should stay technology-neutral, allowing mature technologies to compete fairly or step aside for more cost-effective ones.

This week's 8760 focuses on the United Kingdom. The UK government published some major changes to its flagship renewable auction scheme, the Contracts for Difference (CfD). Key changes include significant increases to the auction price caps, ring-fencing of offshore wind, and new non-price criteria for evaluating bids. The revisions follow the lack of offshore wind participation at the 2023 CfD auction (Round 5) back in September (see here for 8760’s coverage of the auction)

Are these the right changes, and will they produce the intended outcomes? To understand this, this week's 8760 will look at how the CfD auction works, discuss the proposed changes, and analyze their implications.

How the CfD Works

CfD offers a price guarantee. The guaranteed price, also known as the strike price, is determined through annual auctions. Electricity customers top up the generator revenues when wholesale market prices fall below the strike price. The generator returns excess revenues to electricity customers when wholesale market price rise above the strike price. The strike price is determined through the CfD auction process, which runs annually.

At each auction, there are different auction pots intended to allow technologies with the same level of maturity to compete with each other. Due to its poor economic performance in the last auction, offshore wind will be separated from onshore wind and solar into its own pot in the 2024 auction despite the maturity of the technology. Projects in each pot are ranked, and the lowest-bidding projects are accepted until the budget for the pot is exhausted.

During the auction, bids within a pot will be accepted until the pot budget is assessed as having been breached. The budget assessment is based on an anticipated subsidy over the market Reference Price. The Reference Price is set by the government and reflects the expected average market revenues for the technology over time.

Revisions to the UK CfD Scheme

There are three key changes to the auction parameters for the 2024 auction (Round 6).

First, the government has raised the Administrative Strike Price (ASP) for all technologies. This is the maximum the bidders of a particular technology could receive even if the strike price from the pot is higher. The actual prices will likely come significantly below these caps based on recent European auctions. The revised ASPs are (all in 2012 prices):

Offshore wind from £44/MWh to £73/MW;

Floating offshore wind from £116/MWh to £176/MWh;

Geothermal from £119/MWh to £157/MWh;

Solar from £47/MWh to £61/MWh; and

Tidal from £202/MWh to £261/MWh.

Second, as mentioned above, the government is placing offshore wind in a separate auction pot. This means that the clearing price for offshore wind will be based solely on competition among offshore wind projects. It is probably that record-low solar cell prices would lead to solar dominance at the 2024 auction. This change protects offshore wind from competition with cheaper solar and onshore wind projects.

Third, the government is introducing three non-price Sustainable Industry Reward (SIR) criteria for future offshore and floating offshore wind auctions. The SIR criteria aim to prevent Chinese competition ensure sustainability in the UK offshore wind supply chains. The three SIR criteria include:

Investment in deprived areas near offshore wind installation sites;

Spending on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs); and

Minimizing the carbon intensity of the supply chains.

Bidders can submit proposals for subsidies under each of the SIR criteria, and the winning proposals will receive the requested subsidy on top of the auction price. The government is considering requiring future offshore wind CfD bidders to either have a winning proposal in at least one of the SIR criteria or submit a legally binding proposal that meets the government-set minimum standards for each of the SIR criteria.

Administrative Strike Price (ASP) Hike; Great, Now Raise the Budget

Currently, there are 9.3 GW of offshore wind projects that are ready to enter the next auction. What would it take for the entire pipeline to be successful at the next auction?

One possibility is a substantial increase in the Reference Price but this is unlikely. As Figure 1 indicates, the government's latest baseload forecast for 2028 and 2029 is slightly higher than the baseload Reference Prices used in the 2023 CfD auction, but these prices converge by 2030. There may be some room for higher revisions, but the impact will be marginal.

Note: These Reference Prices do not apply to offshore wind. Baseload prices are selected for comparability with the government’s published forecast.

Source: Department for Energy Security and Net Zero

Assuming for now that the government will not raise the Reference Price, the budget for the offshore wind auction pot would need to increase. In the previous auction round, offshore wind was included in the same auction pot as solar and onshore wind, which had a budget of £190 million per year (in 2012 prices). How much would the budget have to increase?

Budget utilization is a function of the Reference Price and the Strike Price. I previously estimated that the current strike price for UK offshore wind projects is likely around £57-59/MWh (2012 prices), which translates to an average of £102-106/MWh over the duration of the 15-year CfD contract starting from 2029, after accounting for inflation indexation at 2.25% per year.

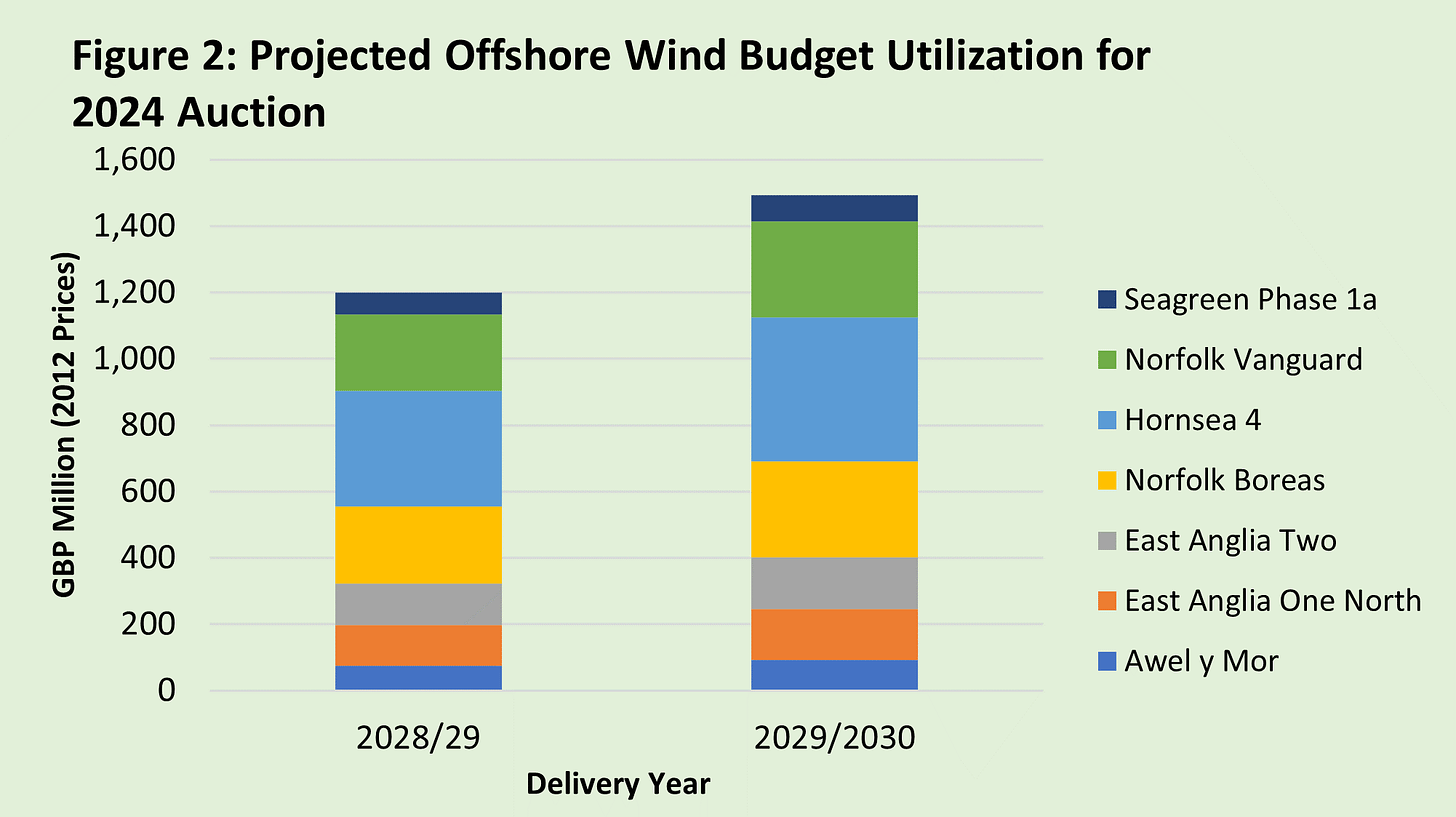

At a £57/MWh strike price, the budget would need to be around £1.5 billion per year for all projects to be successful. This budget would ensure that the 2029/30 auction year budget will not be breached as shown in Figure 2. This required budget could be even higher if Ørsted were to decide to relinquish the CfD contract for Hornsea 3 from the 2022 auction (Round 4) and then re-enter the project into this auction round (Round 6) to secure a higher strike price.

Source: 8760 analysis

One Product, Two Auction Pots; Not So Great

The CfD auction was initially designed so that established technologies would compete together in one pot on a non-discriminatory basis, while less mature technologies with long-term potential were grouped in a separate pot. The principle of competitive bidding on a non-discriminatory basis was emphasized in the European Commission's assessment of the UK state-aid notification of the CfD scheme back in 2013:

“The Commission considers that for the group of the established technologies the selection process is a competitive bidding process open to all generators producing electricity from renewable sources on a non-discriminatory basis. Therefore for this group, it is presumed that the aid is proportionate and does not distort competition to an extent contrary to the internal market, in accordance with point 126 of the EEAG.”

It is difficult to argue that offshore wind, with 13.7 GW installed and another 13.0 GW being installed, is not an established technology. It is established but also expensive. A high-quality but costly product is not a valid reason to protect it from competition with other technologies.

Remunerating for Different Peak Contributions

Some might argue that offshore wind provides different services to the electric grid than onshore wind and solar, primarily its ability to generate more power during peak demand periods (peak capacity). However, CfD generators are not permitted to participate in the capacity market auction, so offshore wind's higher peak contribution is not remunerated. If offshore wind were compensated for its higher peak contribution, would it make a significant difference?

The UK capacity market auction acknowledges differences in peak contribution through the de-rating factor. This factor measures the proportion of a generator's capacity that can be relied upon during peak demand periods. The de-rating factor for solar for the next UK capacity auction is 6.35%, meaning for each 100 MW of solar capacity 6.35 MWh of generation could be counted on during the peak hour. The de-rating factors for onshore wind and offshore wind are 7.03% and 8.69%, respectively. Thus, offshore wind can contribute about a third more capacity during peak periods than solar. Solar has some capacity contribution, despite UK peaks occurring in the evening, because solar generation during the day offsets battery discharges, leaving more battery charge for the peak evening hours.

Using the most recent capacity market clearing price of £63,000/MW/year (2022 prices), CfD solar would have earned around £4.0/MWh (£63,000/MW/year multiplied by 6.35% de-rating and divided by 1,007 MWh annual generation), while onshore wind and offshore wind would have earned £1.2/MWh and £1.0/MWh (£63,000/MW/year multiplied by 8.69% de-rating and divided by 5,545 MWh in annual generation), respectively. Therefore, remunerating CfD generation for different peak contributions would make solar even more attractive. So the argument that offshore wind can provide better grid service than other mature technologies cannot be justified.

Higher Seabed Option Fees Ahead?

Ring-fencing offshore wind could have another unintended consequence. In the UK, offshore wind developers lease the seabed from the Crown Estate, which manages the sovereign's public estate. Previously, seabed allocation was based on competency scoring; the developers with the highest scores won. Since 2021, however, the Crown Estate has been using an auction process, where developers with the highest option fee bids win.

The option fee is an annual payment made by the developer to the Crown Estate for the right to lease the seabed, payable until construction begins, which could be many years in the future. The longer a project remains in the planning stage, the higher the cumulative option fee and the project's final cost, especially in a high-interest-rate environment. These increased costs are ultimately borne by consumers. The Offshore Renewable Energy Catapult estimated in 2021 that the option fee could increase the power price from offshore wind by approximately £10/MWh, based on the highest bid from BP at £154,000/MW/year, if the project is in development for six years. With rising financing costs since 2021, the impact is likely even greater now.

Developers allocated seabed in the 2021 auction will probably not be ready to enter the CfD auction until 2025 (Round 7) at the earliest, so the price impact of the high option fee has not yet been seen. However, placing offshore wind in a separate pot with a higher ASP could prompt another surge in option fee bids, as there is more room to pass these costs onto customers.

A higher option fee could also discourage experienced offshore wind developers from participating in future projects, limiting potential for continued learnings. This was observed in the 2023 German seabed auction, where leases went to oil & gas companies with deeper pockets, such as BP and TotalEnergies, instead of traditional offshore wind developers like RWE, Equinor, and Ørsted.

New Interest-Rate Insensitive Borrowing

Commentators often attribute higher interest rates as a cause for rising renewable project costs. I don't believe that's accurate. High interest rates are a symptom of excess demand for capital. People borrow at higher interest rates because there are still profitable investment opportunities at those rates (I explored this issue around capital formation in this article). As interest rates continue to rise, the economy responds by shifting from investments in projects with high upfront capital intensity to those with more labor intensity. We're already seeing this with private equity, where more money is being deployed into labor-intensive businesses such as HVAC installers, energy consultancies, and energy modeling software.

Proceeding with the 10.7 GW of offshore wind projects is likely to lead to around £18 billion in new borrowings from offshore wind developers. This figure is based on an offshore wind capital expenditure (capex) of £2.37 million per MW and a 70% debt ratio. This £18 billion in borrowing is interest-rate insensitive, as higher interest rates can now be passed on to electricity users through a higher Administrative Strike Price (ASP). For context, UK financial institutions made about £12 billion in net new loans to non-financial businesses in the UK for the entirety of 2022.

Instead of leaving all mature technologies in the same auction pot and letting the market respond to higher interest rates by choosing less capital-intensive options (higher mix of solar and onshore wind and some offshore wind), we are contributing to the ongoing high interest rate environment by pushing more high capital-intensive options. If your mortgage renewal is coming up and you're hoping for a decrease in interest rates, well, good luck!

SIR, More Details Needed on the Sustainable Industry Reward

Details are still lacking with regard to the Sustainable Industry Reward (SIR). The only clear winners from this scheme will likely be consulting firms, which will now be asked to develop SIR proposals, further increasing development costs for offshore wind projects.

Experience from other sectors in the UK with bespoke rewards for non-price criteria has not been positive. In the latest regulated price review for the water sector, the UK water industry regulator received a total of 42 bespoke performance commitment proposals from water companies. The regulator ended up rejecting 35 of the proposals and accepting only 7; a significant amount of consulting expenditure to develop those proposals was wasted no doubt. Similarly, the UK energy industry regulator rejected the majority of over 200 bespoke commitments developed by UK energy network companies at the 2020 price review.

The lesson here is that the government will need to set out clear and quantifiable evaluation criteria for the SIR from the outset. Setting vague criteria and soliciting innovative proposals from developers will likely lead to more complications down the road when it comes time to evaluate the proposals. This could pose a risk of legal challenges over procedural fairness later on.

Conclusion

Following the results of the 2023 CfD auction, the government announced three changes to the auction scheme:

Maximum bid prices (ASPs) are raised for all clean generation technologies except onshore wind. This is welcome and reflective of the current market pricing. However, the auction budget will have to be increased to north of £1.5 billion per year to accommodate all ready-to-go offshore wind projects.

Offshore wind will be segregated into a separate auction pot, insulating it from competition with other technologies. This decision is questionable and may result in unintended consequences, such as higher seabed bids and increased interest rates, both of which could lead to higher offshore wind costs in future auctions. Although offshore wind can contribute more during peak demand compared to wind and solar, the current capacity pricing does not warrant preferential treatment for offshore wind.

The introduction of the Sustainable Industry Reward (SIR) is intriguing, but details are scant. Past experiences in other industries suggest that evaluating bespoke commitments is likely to be a complex task.

In an era of rapidly advancing energy technology, CfD auction designs will inevitably continue to evolve. It is crucial to remember that CfDs should remain technology-neutral, as originally intended. Mature technologies should be able to demonstrate their value in the energy system or yield to other technologies that can facilitate decarbonization at lower costs.